In 2015, an apartment complex in Fayetteville, NC evicted 156 tenants. One might think perhaps the neighborhood was gentrifying, and this landlord was emptying their complex of all the low-income tenants: a one-time turnover. Yet, the complex evicted 137 tenants, on average, in each of the prior eight years. This one building evicted nearly five percent of all tenants who were removed from their homes in the city of Fayetteville during a ten-year span.

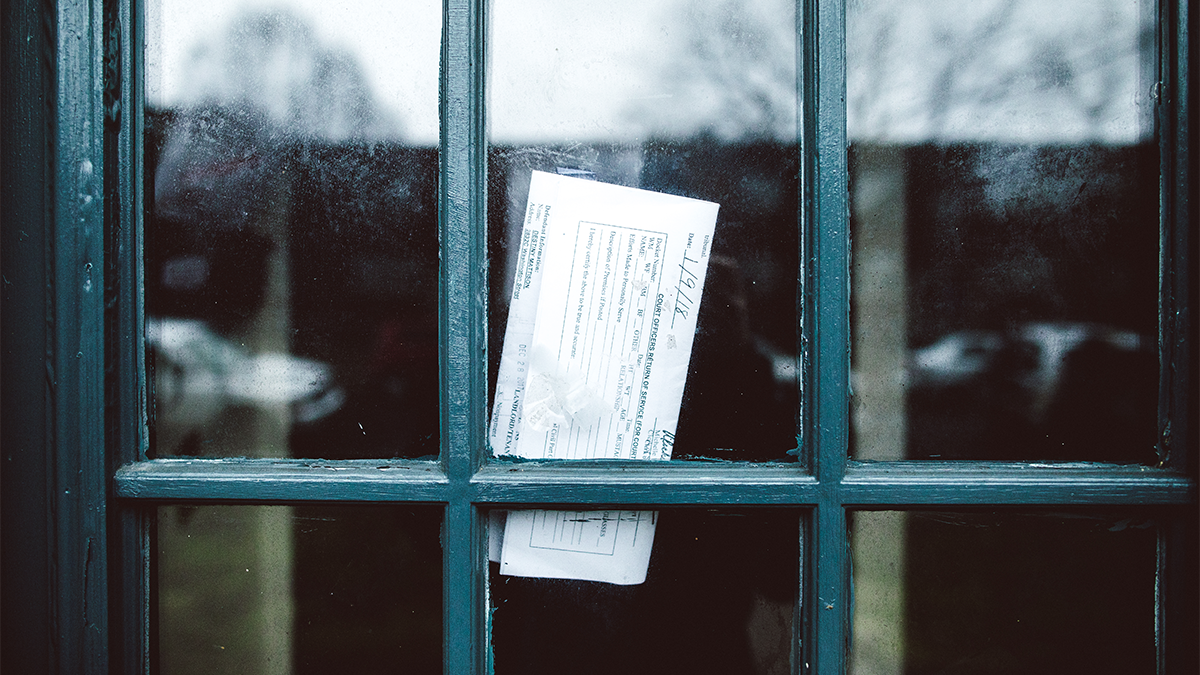

In order to design policies that could anticipate and prevent tenants from being evicted, the Eviction Lab analyzed the locations of evictions over time, hoping to detect a meaningful pattern. Based on our analysis of 17 cities, evictions occur in the same neighborhoods and even the same street blocks year after year. Rather than occurring when neighborhoods are destabilized, through gentrification or other types of neighborhood change, eviction remains the status quo in pockets of American cities.

In order to understand why evictions occur in the same places again and again, we zoomed in on three cities—Cleveland, Ohio, Fayetteville, North Carolina, and Tucson, Arizona. We identified the buildings driving evictions over a ten-year period and found that displacement is common in some neighborhoods because a handful of landlords (and therefore buildings) evict large numbers of tenants every year. We located evictions, not just at the neighborhood level, but at the building level. As few as 100 buildings drove one in six evictions in Cleveland and two out of every five evictions in Fayetteville and Tucson. Most landlords evict tenants rarely, if they ever do—even in neighborhoods that have high overall eviction rates. Yet, a small set of landlords displace large numbers of tenants, year after year.

Curious how these landlords might drive the overall level of evictions citywide, we tracked the number of evictions that buildings produced each year. Setting aside the large number of residential buildings that were never connected to an eviction, we distinguished between buildings where landlords evict infrequently—perhaps only a couple of times in a decade—from those where landlords produced consistent numbers of evictions—multiple tenants were evicted in every year. As demonstrated in the figure below, these ‘routine evictors’ inflate the overall level of instability in each city.

These findings yield two key insights into the eviction crisis that cities and service providers can use to design effective interventions. First, our research suggests cities and states can anticipate evictions because they are produced by the same landlords year after year. Second, because just a few landlords account for large numbers of all evictions, nonprofit organizations and local governments can make outsized progress toward addressing the eviction epidemic by targeting the landlords who drive the eviction crisis.

Specifically, cities and service providers might use this information to:

While creating an all-inclusive rental assistance program is outside the budgetary capability of many municipalities, preventing the creation of mass evictions, poverty, and homelessness are well within their reach, particularly if they focus their efforts on top evictors.